Recently, I’ve been swimming in Chekhov. I didn’t plan it this way.

The first plunge happened over coffee with a friend who finished grad school almost a year ago at a major MFA program here in New York City. We chatted about her emergence from an intensive three-year conservatory. Describing her experience, she invoked Nina from Chekhov’s The Seagull.

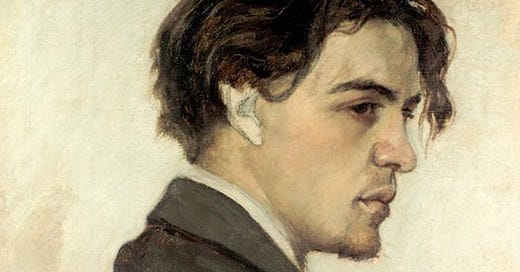

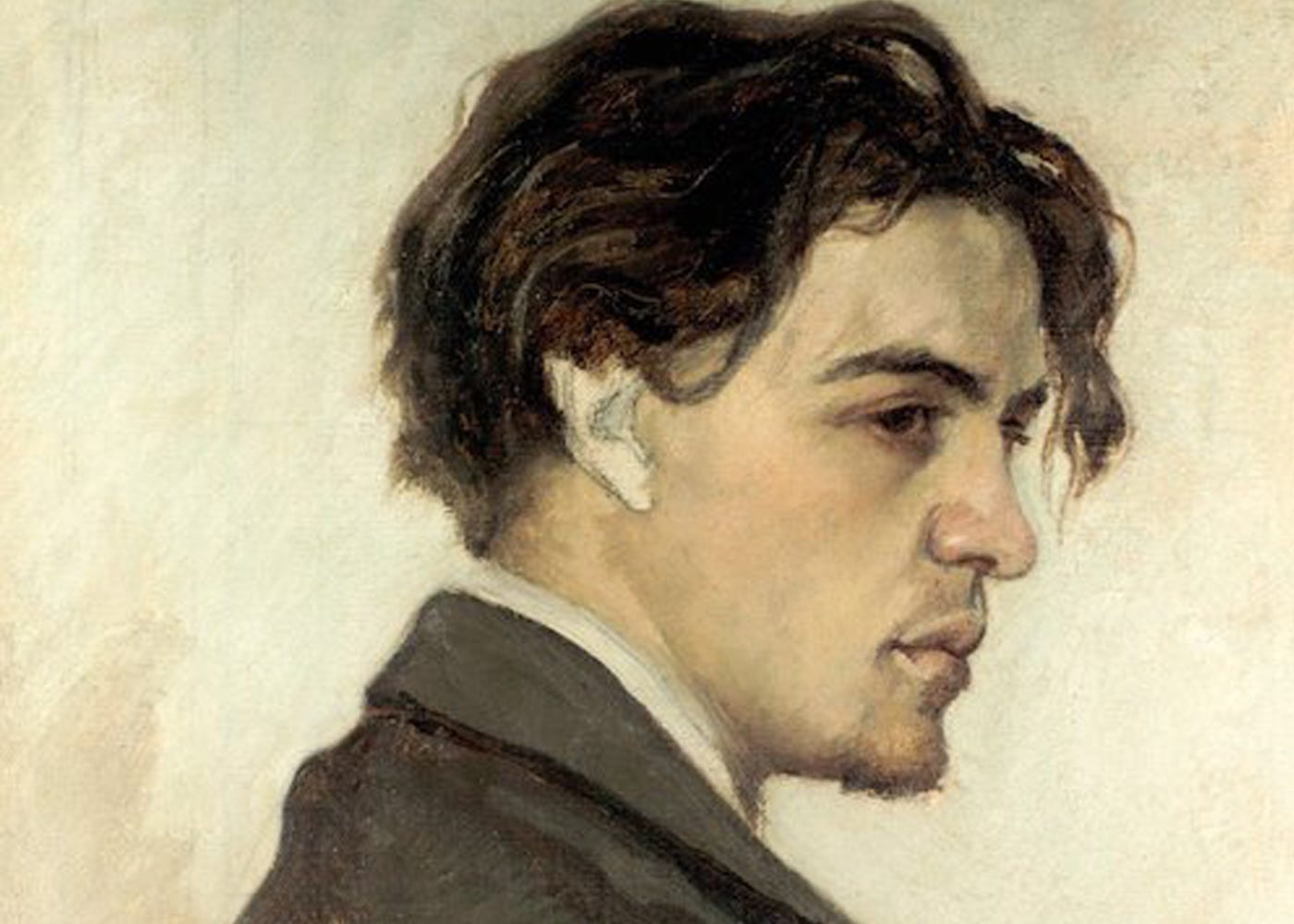

My ears perked up because I lived in Russia for a couple of years, translated and staged most of Chekhov’s major plays, and have taught his work in some form or other for the past decade. With startling clarity, my friend took me inside Nina, reminding me of her grit and resolve. Over two years (four acts in Chekhov’s play), Nina goes from ardent aspirant to a professional, forged-in-the-fire. I felt moved to see Chekhov’s work take such hold on someone.

A few days later, two brilliant students in my acting course at Pace took on Nina’s scene with Kostya from Act IV of The Seagull. On the heels of my conversation with my actor friend, I coached the scene more surely than ever. Intentions and structure snapped into place, and the performance, even in the hands of young actors, took on a beautiful and moving shape.

And a few days after that, I met a new friend, Forrest Malloy, for lunch. Forrest is one of those people who wears their accomplishments lightly (MFA actor from Julliard Drama Division, playwright, compassionate and amazing teacher). I teach theater with Forrest at Pace University, and we met up to talk about a new play he’d written called Nina.

It’s rare that a play makes you feel seen and felt in the way that this one did.

Nina treats five women in a conservatory MFA acting program in NYC. It’s set in a dressing room. Four acts, four moments in their final semester. The last act takes place during a performance of The Seagull’s Act IV. In Nina, episodes from these women’s lives echo Nina’s experience of becoming an actress in The Seagull. It’s a great play; I can’t wait for it to find an audience, and a full production.

These brushes with The Seagull got me thinking about the artist’s journey. Like Nina, many young people believe this journey means transcending loneliness and living in full connection, artistic ecstasy. It makes sense. Performing satisfies part of our deepest human need—to see and be seen—and who wouldn’t want to be seen all the time?

But The Seagull is also about the risks of all that seeing. Nina’s refrain, “I’m a seagull…that’s not it,” expresses her fear of being destroyed by those who, seeing her, want to possess and admire her, like the stuffed seagull in Act IV, shot by Kostya and stuffed at Trigorin’s command.

Nina says she’s “not afraid of life” when she’s onstage. The experience of being fully seen gives her meaning and purpose. But the same need to be seen that lures aspirants to the stage can also cause soul wounds, even death. Kostya’s need to be seen was so powerful that, unfulfilled, it destroyed him.

For me, The Seagull asks how to manage this profound human need for connection when it goes unmet. When an actor performs badly and knows it, then what? When a writer hammers out a new script that feels deformed and unsalvageable, then what? When a person feels essentially unlovable—unworthy of being seen—then what?

The main thing, Nina says, is to endure. An artist strives to express herself fully while navigating systems that categorize, commodify, possess, or reject; audiences who create celebrity and lock an artist into a singular identity; evaluations that deem one person worth seeing and another less so. Likes, clicks, reviews, critics’ picks, adoring or derisive comments, all measure worthiness of being seen. Within and despite all this, the artist must endure, believing even in the well of her own solitude, that she is worth being seen.

Each of us is worth seeing, after all.

I love Chekhov with my whole heart because he sees artists so profoundly and, in his 44 years, came to some startling revelations about art-making and its relationship to love and human connection.

There are moments of connection make you feel unafraid of life. They make me feel unafraid of life.